Precision Medicine

In Pursuit of Biomarkers for Diseases of the Mind

Researchers at Houston Methodist turn toward the gut microbiome for biomarkers predictive of the severity of anxiety and depression.

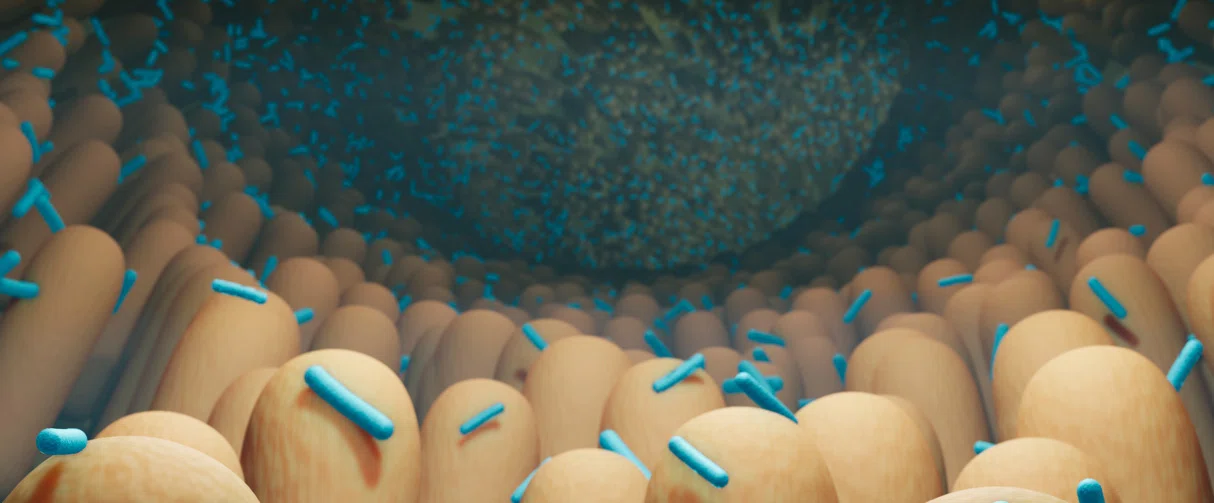

Of the staggering quadrillion-quadrillion bacteria sprawling on planet earth, about a trillion enjoy the comfort of our gut, slightly outnumbering human cells in the body by a trillion. This truce between humans and gut bacteria over the course of evolution has resulted in an intimate symbiotic relationship that is essential for our health and well-being. But the suite of services provided by our gut microflora goes beyond maintaining metabolic homeostasis and defending against pathogens: The gut microbiome, sometimes referred to as the “forgotten organ”, also talks with our brain.

The digestive tract and the central nervous system communicate along pathways that are together referred to as the gut-brain axis. Through the nervous, endocrine and immune systems, the gut microbiome, consisting largely of bacteria and their metabolites, influences and is influenced by the brain.

Alok Madan, PhD

Professor of Psychology in Psychiatry and Behavioral Health at Houston Methodist

“It's a bi-directional relationship, what's going on in our brain has a direct bearing on our gut microbiome and then, what's going on in our gut has a direct bearing on how we feel, what we think, and in some ways, what we do,” said Alok Madan, PhD, professor of psychology in psychiatry and behavioral health.

At Houston Methodist, his team is tackling the complex task of identifying which ones, among the thousands of gut bacterial strains, affect conditions of the mind, like depression and anxiety.

The concept of reciprocity of the gut and brain was first recognized more than 300 years ago. In 1795, Scottish physician, Robert Whytt, coined the term “nervous sympathy” upon observing that internal organs, including the gut, are connected to the brain through a network of nerves and their endings. By extension, physicians of that time deeply appreciated that an unhealthy gut could eventually lead to an unhealthy mind. However, this holistic view of mental health took a backseat in the 19th century with the popularity of medical specialization, enabling physicians to focus on the health of individual organs. By the 20th century, however, the rise of non-infectious diseases prompted reinvestigations of the influence of lifestyle on health and thus, the holistic view of the gut and brain started gaining prominence in scientific thought once again.

Today, there is increasing evidence of the gut microbiome’s influence on neurological conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease, stroke and autism, driving research into targeting the microbiome for therapeutic interventions. The gut microbiota, has thus, also received attention for managing mental illnesses for which reliable biomarkers are currently lacking.

“Diagnosis for a psychiatric disease is typically based on self-reports and observation. And then, most psychiatric interventions are modestly effective with some patients even showing treatment resistance,” said Madan. “In pursuit of biomarkers for these diseases, we wanted to look at patients early in their hospitalization to see what their gut microbiome looked like and how that information related to their clinical presentation.”

Such psychiatric disease-specific changes in the microbiome, when unraveled, might be linked to why some patients may respond to treatment while others do not, he added.

But how do we acquire a unique, yet dynamic, microbiome fingerprint in the first place? Rewinding the clock, a growing fetus develops in a germ-free environment in the womb and is first exposed to microbes during birth. In fact, babies born vaginally are inoculated by different strains of microbes compared to those born through C-sections – a difference also conserved in the newborns’ gut for up to three months. Although the first few years of life are critical to the microbial colonization of the digestive tract, diet and lifestyle closely modulate the bacterial populations, giving each adult an exclusive gut microbial signature.

Further, the microbiome is quite resilient to perturbations, allowing the gut to retain certain important bacterial strains for long periods. However, chronic psychiatric diseases can make the gut microbiome vulnerable, an observation repeatedly confirmed by both human and animal studies.

“Mice with depression-like behaviors or anxiety-like behaviors show a general trend in their microbiome – a homogenization of their gut bacteria,” said Madan. “We see this result in our hospitalized patients too. There is a decrease in the variety of gut bacteria with a disease state, whether that's depression, anxiety, psychosis, take your pick.”

This reduction in gut biodiversity is observed despite differences in the patient’s geographical location, cuisine and lifestyle, suggesting a more direct link to the individual’s mental health. Since many of these patients also show treatment resistance, Madan’s team investigated which strains out of roughly 10,000 gut bacterial species could be involved in the limited treatment benefit for anxiety, depression or both.

For their data analysis, Madan’s Houston Methodist team collaborated with scientists at Baylor College of Medicine. Their collaborators' sophisticated analytic approach, called DiffCoEx, initially used to identify biomarkers in large cancer data sets, was repurposed to identify co-expression patterns of gut bacterial genes and metabolic pathways that were associated with treatment-resistant anxiety and depression.

“It’s like finding a needle in a haystack,” said Madan. “But with our advanced data analytical technique, we were able to pare down candidate bacterial taxa from 10,000 to 43. That's a huge reduction.”

The researchers then took a step further by perusing the scientific literature and asked whether these 43 candidate bacterial strains were associated with medical terms relevant to depression and anxiety, such as inflammation and dysbiosis. This review revealed that the shortlisted 43 bacterial taxa tend to be pro-inflammatory. Furthermore, these strains were associated with both mental health conditions, suggesting that depression and anxiety are overlapping conditions in which the gut microbiome-instigated inflammation plays a key role.

Madan speculated that inflammation could increase disease severity, and consequently standard treatments could be rendered less effective because there is a higher dose of the disease. Alternatively, inflammation might require being addressed separately, which current treatments are not designed to do. In these patients, gut biomarkers can play an important role:

“A gut-based marker can potentially identify people that might not respond to the standard course of treatment much earlier, as opposed to having them go through the whole course of treatment that may not work,” said Madan.

These findings are published in the journal Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry.

The researchers noted that their study begins to examine the part played by the gut bacteria in the pathology of mental illnesses, and further research is needed to understand the exact biological mechanisms by which the microbiome affects the development, maintenance and treatment of psychiatric disorders.

At Houston Methodist, the team will embark upon investigating if the gut microbiome changes with an alleviation of mental health symptoms. These longitudinal studies will look at the gut microbiome assemblages at different time points during treatment. Such investigations, they said, are much needed to answer if symptomatic improvement occurs after a change in gut bacterial population or the other way around, where gut bacterial change precedes symptomatic improvement. Madan’s group also plans to extend their research into other frontiers such as the gut microbiome’s involvement in opioid dependence and response to treatment.

“It’s a challenge to study the microbiome,” said Madan. “We need somebody with expertise in mental health, somebody with a microbiology background and a data analytics expert. But we were able to assemble a team with diverse talents and are doing our part in slowly unlocking the secrets of the gut microbiome.”

Madan acknowledges Houston Methodist’s John S. Dunn Foundation which has provided him with an endowed chair in support of brain-gut research. This research was partially supported by the Houston Methodist Foundation, The Menninger Clinic Foundation and Baylor College of Medicine’s Alkek Center for Metagenomics and Microbiome Research. Further support is provided by The Cancer Prevention Institute of Texas and grants from the National Institutes for Health.

Dominique S. Thompson, Chenlian Fu, Tanmay Gandhi, J. Christopher Fowler, B. Christopher Frueh, Benjamin L. Weinstein, Joseph Petrosino, Julia K. Hadden, Marianne Carlson, Cristian Coarfa, Alok Madan, Differential co-expression networks of the gut microbiota are associated with depression and anxiety treatment resistance among psychiatric inpatients, Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, Volume 120, 2023, 110638, ISSN 0278-5846, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2022.110638.

Vandana Suresh, PhD

February 2023

Related Articles