Clinical Research

Houston Methodist Conducts First-Ever Study into a Challenging Condition

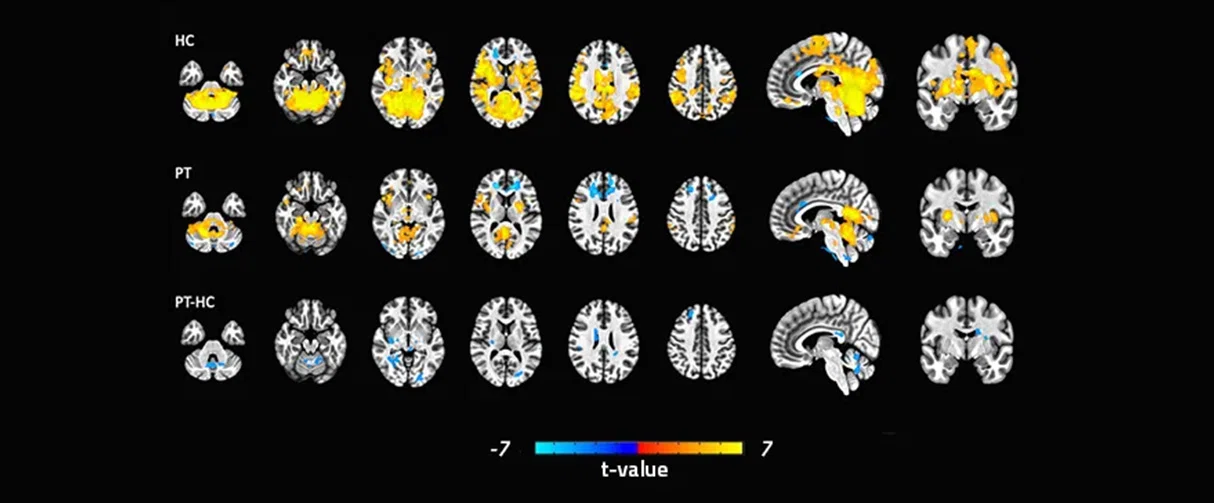

Functional Defecatory Disorder study finds key differences in activation patterns of patients' brains

Functional defecatory disorder (FDD) is a challenging condition for patients and clinicians alike, but a new study that shows differences in related activation patterns of patients' brains may help streamline diagnosis and treatment, offering faster relief.

Characterized by a frequent and powerful urge to evacuate one's bowels and an inability to effectively do so, FDD primarily affects women and can lead to chronic constipation, pain, disruption to daily life and even hospitalization.

The study, published in Neurogastroenterology & Motility, is the first of its kind to investigate the central control mechanism of defecation in humans using concurrent functional MRI recording and rectal manometry.

"Until now, research on functional defecatory disorder has concentrated almost exclusively on colorectal anatomy and peripheral mechanisms," said Eamonn Quigley, MD, director of the Underwood Center for Digestive Health at Houston Methodist and co-author of the study. "Likewise, clinicians and patients can spend months seeking and ruling out physical causes, using expensive and sometimes invasive tests. This study offers compelling evidence that we should be focusing on the brain-gut connection and brain-directed therapies for the highest chance of success."

To investigate the brain-gut connection, researchers recruited 15 healthy female control subjects and 18 women with FDD to undergo a balloon expulsion test and functional MRI at the same time. The goal: identify the specific regions of the brain involved in defecation and determine if activity in these regions is different in FDD. Such activity was measured by blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signals.

Eamonn Quigley, MD

David M. Underwood Chair of Medicine in Digestive Health, Department of Medicine

Professor of Medicine, Academic Institute

Director, Lynda K. and David M. Underwood Center for Digestive Disorders

Houston Methodist

Weill Cornell Medical College

There were differences in key regions of the brain that have to do with executive-cognitive function, coordination and emotion, which suggests some lack of communication and/or coordination between the brain and the pelvic floor and sphincter muscles. But it doesn't necessarily explain how or why this occurs. Are these individuals receiving the wrong signals from down below or are they sending the wrong signals down below, or does it go both ways? Is it caused by psychological stress or is the person's functional defecatory disorder causing them psychological stress?"

Eamonn Quigley

David M. Underwood Chair of Medicine in Digestive Health,

Department of Medicine

Professor of Medicine, Academic Institute

Director,

Lynda K. and David M. Underwood Center for Digestive Health

Houston Methodist

Weill Cornell Medical College

Simulated defecation was associated with activation of regions of primary and supplementary motor and somatosensory cortices, homeostatic afferent (thalamus, mid-cingulate cortex and insula) and emotional arousal networks (hippocampus and prefrontal cortex), occipital and cerebellum along with deactivation of right anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) in controls.

Study participants with FDD had fewer brain regions engaged during defecation and significantly decreased BOLD signals in areas related to executive-cognitive function (insula, parietal and prefrontal cortices). They showed higher activation in the right ACC than healthy study participants. Otherwise, brain activation patterns were similar when tightening the anal sphincter.

Although further research is needed to explore these questions, the study's important insight, according to Quigley, is that the brain plays a critical role in medicating this process. This provides further validation for the role of brain-directed therapies like biofeedback as the mainstay of treatment for FDD.

"Achieving an effective bowel movement is more complicated than most people realize," Quigley said. "It requires the subtle coordination of a variety of muscles, the nerves that supply those muscles, the brain and the signals the brain is sending to either contract or relax."

Biofeedback is a form of physical therapy that uses neuromuscular conditioning techniques to coach patients on the dynamics of defecation. Studies have shown it is effective in up to 80% of patients with FDD.

"I hope physicians will review our study and feel empowered to recommend biofeedback right out of the gate, rather than feeling the need to go down all the other potential avenues first," Quigley said. "Retraining the mind and body takes time, but it offers real relief for a condition that significantly impacts quality of life."

Eden McCleskey, August 2022

Leila Neshatian ,Christof Karmonik, Rose Khavari, Zhaoyue Shi, Saba Elias, Timothy Boone, Eamonn M. M. Quigley First published: 27 April 2022 https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.14389