Liver Failure Avengers

Houston Methodist Researchers First in World

Liver Failure Avengers

Houston Methodist Researchers First in World

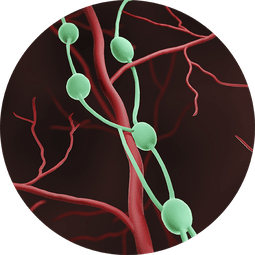

Meet the lymph node.

They are best described as small, bean-shaped organs. Think the size of a pea. The power that they possess can quite possibly lengthen the life span of a patient with liver failure by replicating the function of a healthy liver tissue and reversing the signs and symptoms this disease.

Lymph nodes are found at the convergence of major blood vessels in the body. An adult will have approximately 600-800 nodes—varying by person—located in the neck, armpit, chest, behind the ear, abdomen and groin. These organs are tasked with filtering substances in a person’s lymph fluid (proteins, minerals, nutrients, fats, white blood cells, damaged cells, cancer cells, viruses and/or bacteria).

Houston Methodist researchers are now in a Phase 2a Clinical Trial—Safety, Tolerability, and Efficacy of Hepatocyte Transplantation into Periduodenal Lymph Nodes Among Subjects With End-Stage Liver Disease. Houston Methodist is one of two study sites partnering with LyGenesis, Inc. Boston’s Tufts Medical Center is the other participating site.

Since enrolling the first patient, Mobley’s team has been inundated with people asking to participate in this study, from as far as Europe to Australia and across the U.S. According to the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), more than 10,000 liver transplants were performed in 2023—the most ever in a single year; however, more than 1,700 patients die annually while on a liver transplant waitlist.

Constance Mobley, MD, PhD, FACS

Under the leadership of Constance Mobley, MD, PhD, FACS, researchers have successfully performed a first-in-human miniature liver hepatocyte transplant to change a patient’s lymph nodes into ectopic miniature livers.

“What’s so exciting about this study is that these types of studies have never been performed in patients,” emphasized Mobley, Associate Director, J.C. Walter Jr. Transplant Center. “We are the first hospital in the world to successfully inject these cells into a human. We always hear that Houston Methodist is leading medicine; in this instance, we actually are the first in the world to accomplish this goal.”

We are the first hospital in the world to successfully inject these cells into a human. We always hear that Houston Methodist is leading medicine; in this instance, we actually are the first in the world to accomplish this goal.

Constance Mobley, MD, PhD, FACS

The team has dosed three patients who are currently on a transplant waitlist, using their lymph nodes as living bioreactors to regenerate an ectopic organ. The selected patients must have a Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score that is greater than 10, but less than 25 at the time they are enrolled in the study. The goal is to have a total of 12 patients for the study, which began in 2022.

Mobley’s colleague, Sunil Dacha, MD, MBBS, performs an endoscopic ultrasound to locate the lymph nodes in the periportal area. Patients who are experiencing end-stage liver disease tend to have enlarged lymph nodes in the area between the stomach, liver and duodenum. Once Dacha locates a lymph node in that area, he endoscopically injects that lymph node with the liver cells.

Sunil Dacha, MD, MBBS

“The procedure is simple; however, the difficulty lies in identifying the nodes around the liver due to their size—one centimeter or less. They are not easy to find, but with meticulous examination, we’ve been able to successfully perform three procedures,” said Dacha, Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine. “All three patients have done well. What we are doing is a unique thing. Only at Houston Methodist in the world.”

The first stage of this study is to meet the FDA requirements of safety, tolerance and efficacy.

“With our initial patient cohort, we want to ensure that their lymph nodes are functioning like livers,” said Mobley. “Our primary endpoint is safety and tolerability.”

Presently, Mobley’s team is monitoring their three patients for a year to note any changes in their baseline liver function with the hope their liver is becoming healthier.

If this first-in-class allogeneic regenerative cell therapy obtains FDA approval, it would enable one donated liver to treat dozens of end-stage liver disease patients, which could vastly affect the organ supply and demand imbalance for patients suffering from liver failure.

“There are so many patients waiting, and many die waiting,” she said. “There’s such a great need for the success of this study because there aren’t enough organs for the number of patients who are in need. Once we are successful in this study, the number of patients who we will be able to treat and save from liver disease will be immeasurable.”

Mobley also noted how this can be a game-changer when treating patients with liver failure who may have additional underlying conditions that can be a barrier to receiving a liver transplant.

“Ultimately, my hope is that using liver cells will allow us to rescue patients who are extremely sick and can’t tolerate surgery,” she said. “Theoretically, we could get so good at this that maybe patients wouldn’t need liver transplants, which would be incredible.”